Connecting Cultures: Balinese Character and the Computer

“We were compelled to economize on motion-picture film, and disregarding the future difficulties of exposition, we assumed that the still photography and the motion-picture film together would constitute our record of behavior. [”Notes to the Photographs,” in Bateson and Mead, 1942 (italics Bateson’s)]

“If inventions are made that transform numbers, images and texts from all over the world into the same binary code inside computers, then indeed the handling, the combination, the mobility, the conservation and the display of the traces will all be fantastically facilitated. When you hear someone say that he or she ‘masters’ a question better, meaning that his or her mind had enlarged, look first for inventions bearing on the mobility, immutability or versatility of the traces; and it is only later, if by some extraordinary chance, something is still unaccounted for, that you may turn towards the mind.” (Latour, 1986 (italics Latour’s)).

The Bali Research

Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead arrived in Bali in March of 1936 to study the relationship between forms of social organization and types of temperament or character structure. They had developed a complex theory about the way societies emphasized one or another of the temperamental types available in the human organism, and a typology of such types (divided by gender) and the situations that went with them.

What if human beings, innately different at birth, could be shown to fit into systematically defined temperamental types, and what if there were male and female versions of each of these temperamental types? And what if a society—by the way in which children were reared, by the kinds of behavior that were rewarded or punished, and its traditional depiction of heroes, heroines, and villains, witches, sorcerers, and supernaturals— could place its major emphasis on one type of temperament, as among the Arapesh and the Mundugumor, or could, instead, emphasize a special complementarity between the sexes, as the Iatmul and the Tchambuli did? And what if the expectations about male-female differences, so characteristic of Euro-American cultures, could be reversed, as they seemed to be in Tchambuli . . . (Mead, 1972, p. 216)

Having placed the societies they already knew in that typology, they could now choose cases to fill in its missing cells.

We had chosen Bali with knowledge and forethought as the culture we wanted to study next in order to obtain material on one temperamental emphasis we had only hypothesized must exist. We had seen just enough material in films and still photographs, had heard just enough of the music studied by Colin McPhee, and had read just enough in Jane Belo’s careful records of the ceremonies with which the Balinese greeted the terrible disaster of the birth of twins to assure us that this was the culture we wanted to work on. (ibid., p. 224)

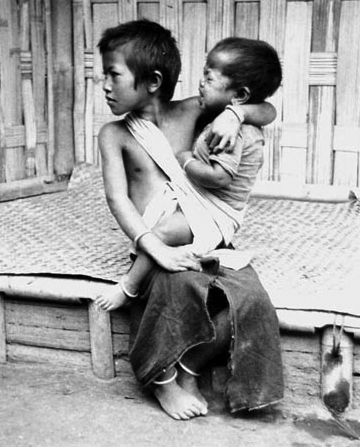

During their two years of fieldwork they made 25,000 still photographs and shot 20,000 feet of 16mm motion picture film. They usually worked together: Mead made verbal notes and Bateson photographed moving pictures and stills.[1] Their Balinese secretary, Made Kaler, kept a record in Balinese. The time and date were written on each role of film when it was placed in the camera and again when it was removed. In this way the images could be matched with the verbal records whose time was also recorded. They did not make sound recordings, relying instead on musical recordings made by others. (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p.49 and Mead, 1972, p. 231)

Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis, the book Bateson and Mead published in 1942, contains 759 of the still photographs, reproduced in one hundred Plates. Each Plate consisted of two facing pages. One page contains from four to thirteen photographs, and its facing page a general statement of theory, a description of the context in which the photographs in the plate were made, and detailed captions for the individual photographs. Bateson and Mead never solved the problem of incorporating the motion picture film[2], or of making it convenient for readers to follow the multiple paths through the data their careful cross-referencing made possible.

Because the technical apparatus they needed to use motion picture film and still photographs together is now available, it is useful to examine their methods and their reasons for adopting them, and to examine the implications of their methods of analyzing and presenting ethnographic work.

Why They Made Photographs in the First Place

In the introduction to the book, Mead says the methods she and Bateson had used separately in previous work seemed inadequate to describe the aspects of culture and behavior they were studying: “. . . from 1928 to 1936 we were separately engaged in efforts to translate aspects of culture never successfully recorded by the scientist, although often caught by the artists, into some form of communication sufficiently clear and sufficiently unequivocal to satisfy the requirements of scientific enquiry.” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. xi)

Using their own past work as examples, Mead outlines the specific dissatisfactions she and Bateson had with conventional methods of describing phenomena, conventional ways of doing and presenting fieldwork. Of her three previous books, she says:

As no precise scientific vocabulary was available, the ordinary English words were used, with all their weight of culturally limited connotations, in an attempt to describe the way in which the emotional life of these various South Sea peoples was organized in culturally standardized forms. This method had many serious limitations: it transgressed the canons of precise and operational scientific exposition proper to science; it was far too dependent upon idiosyncratic factors of style and literary skill; it was difficult to duplicate; and it was difficult to evaluate.

Most serious of all, we know this about the relationship between culture and verbal concepts—that the words which one culture has invested with meaning are by the very accuracy of their cultural fit, singularly inappropriate as vehicles for precise comment upon another culture. (Ibid.)

Of Bateson’s work:

Parallel with these attempts to rely upon ordinary English as a vehicle, the approach discussed in Naven was being developed—an approach which sought to take the problem one step further by demonstrating how such categories as ethos, there defined as “a culturally standardized system of organization of the instincts and emotions of individuals,” were not classifications of items of behavior but were abstractions which could be applied systematically to all items of behavior.

The first method has been criticized as journalistic—as an arbitrary selection of highly colored cases to illustrate types of behavior so alien to the reader that he continues to regard them as incredible. The second method was branded as too analytical—as neglecting the phenomena of a culture in order to intellectualize and schematize it. The first method was accused of being so synthetic that it became fiction, the second of being so analytic that it became disembodied methodological discussion.

In this monograph we are attempting a new method of stating the intangible relationships among different types of culturally standardized behavior by placing side by side mutually relevant photographs. Pieces of behavior, spatially and contextually separated . . . may all be relevant to a single discussion . . . the same emotional thread may run through them. To present them together in words, it is necessary either to resort to devices which are inevitably literary, or to dissect the living scenes so that only desiccated items remain. (Ibid., pp. xi–xii)

They settled on photographs and motion-picture film as ways to expand their descriptive vocabulary, not as a replacement for other tools, but as an additional tool. They saw different media as different ways of getting at the same thing, enabling different kinds of describing, expressing, and knowing.

Additional forms would allow them to describe behavior more precisely, to use the word Mead repeats three times in two paragraphs of the Introduction to define the kind of language proper science requires. What qualities, for their purposes, make a description more precise?

A more precise description requires a form that conveys an interconnected sense of the wholeness of experience, preserves a kind of simultaneity, presents simultaneously events that had occurred simultaneously, not isolating elements but making the view more systemic. It requires a form that records fine detail, the images being detailed and complex enough that many more connections and greater understanding can be extracted from them than written notes can itemize.

They valued the potential of images for describing, simultaneously, specific and minute details of surface, gesture, and spatial relationships, and their alterations over time, because, for their purposes and according to their theory of knowledge, stringing these aspects of events out linearly in text would be a distortion, .

Plate 16, “Visual and Kinaesthetic Learning II” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. 86-7), for example, contains a sequence of eight photographs of a dance lesson: teacher and students surrounded by the orchestra. The master guides the student visually and kinesthetically, not verbally. The plate helps Bateson and Mead establish two important points about Balinese character formation. “From his dancing lesson, the pupil learns passivity, and he acquires a separate awareness in the different parts of the body.”

Each image in the plate establishes relative spatial and size relations rapidly. The images give us detailed nuances of facial expression, body tension and position, and often the physical location and larger context of other people, the musicians, the instruments, simultaneously “frozen” at a particular moment.[3] It’s all there at once, eight images combined on the flat surface of the page for the viewer to study individually and compare with one another.

The emphasis on portraying relationships simultaneously also determines, in part, the composition of the individual images. Bateson composed many of the photographs, we can see, so as to “preserve the wholeness of each piece of behavior.” Particular aspects of a scene that interest him are seldom isolated in the frame by such compositional devices as selective focus. On the contrary, he apparently made no attempt to exclude background detail, or the heads, arms, legs, and other body parts of anyone who happened to walk by from the frame. In fact, the notes sometimes say whose head or foot it is. These “accidents” only enhanced the value of the image as data.

Putting Photographs and Film Together

After returning to the United States for further analyses of the material and arrangement of it into a presentable form, the “difficulties of expositon” could no longer be “disregarded” as Bateson and Mead confronted the impossibility of presenting the two formats together. They had hoped to use the film and the still images together, both in their analysis and in its later presentation. In the 1930s, when the work was produced, they couldn’t do it. The technology at the time being what it was, no common format existed in which the two media could be combined. In his “Notes to the Photographs” in the book, Bateson expresses disappointment that some plates are, in his view, inadequate because they lack particular images that were recorded on motion-picture film. “The present book is illustrated solely by photographs taken with the latter [still camera], and as a result, the book contains no photograph of a father suckling his child at the nipple, and the series of kris dancers (Pls. 57 and 58) leaves much to be desired.” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. 51)

Vaguely aware of this problem while in the field, they had conducted their research as if today’s computer imaging technology—which makes it possible to digitize photographs and film (still images and moving images) and present them together, along with sound and extensive text, in the same piece of work (together on one flat surface)—was available to them in 1936, which it was not.

It might seem odd, or even naive, for Bateson and Mead to have ignored these problems, until you consider the degree to which they invented their photographic methods of record and description in the course of doing the research.

When we planned our field work, we decided that we would make extensive use of movie film and stills. Gregory had bought seventy-five rolls of Leica film to carry us through the two years. Then one afternoon when we had observed parents and children for an ordinary forty-five minute period, we found that Gregory had taken three whole rolls. We looked at each other, we looked at the notes, and we looked at the pictures that Gregory had taken so far and that had been developed and printed by a Chinese in the town and were carefully mounted and catalogued on large pieces of cardboard. Clearly we had come to a threshold—to cross it would be a momentous commitment in money, of which we did not have much, and in work as well. But we made the decision. Gregory wrote home for the newly invented rapid winder, which made it possible to take pictures in very rapid succession. He also ordered bulk film, which he would have to cut and put in cassettes himself as we could not possibly afford to buy commercially the amount of film we now proposed to use. As a further economizing measure we bought a developing tank that would hold ten rolls at once and, in the end, we were able to develop some 1600 exposures in an evening.

The decision we made does not sound very momentous today. Daylight loaders have been available for years, amateur photographers have long since adopted sequence photography, and field budgets for work with film have enormously increased. But it was momentous then. Whereas we had planned to take 2,000 photographs, we took 25,000. It meant that the notes I took were similarly multipled by a factor of ten, and when Made’s notes also were added in, the volume of our work was changed in tremendously significant ways. (Mead, 1972, p. 234)

They had very specific reasons for using visual materials and anticipated they would be significant to their work. But the details of the subject matter, compositon, and other particulars of making and using the images were worked out in the field: one afternoon Bateson used the camera in a way they didn’t anticipate. They were innovating and experimenting, and they knew it.

Photographs as Descriptive Records From Which to Form Hypotheses

“We treated the cameras in the field as recording instruments, not as devices for illustrating our theses.” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, ibid., p. 49)

Bateson and Mead saw still photographs and motion-picture film as forms of description. As descriptions, photographic images have all the limitations of viewpoint, selectivity, and contextualization of other kinds of description: verbal accounts, tape recordings, drawings. Images are finely detailed maps of selected 3D space at a particular place and instant in time or, in the case of film, over a specific period of time, mapped point for point onto a 2D surface. These maps can be carried to distant places and studied at later times, an activity that necessarily attaches a more complex notion of time to the image.

But what images describe—their meaning, what they “show”—is an interpretation. Bateson and Mead did not take that meaning to be self-evident. Rather, they considered the connections, explanations, and interpretations the photographs suggested as hypotheses to be explored further, as they directed the photographing more specifically to the new ideas and connections suggested by earlier images.

Plate 54, “Girls’ Tantrums” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. 162-3), contains thirteen photographs, the first two of the same incident, a tantrum in the road, photographed early in the fieldwork. In the first photograph, a young girl is shown screaming, with “her hands raised to her head in a posture closely related to those of the boy in PL. 53.” In the caption to the second photograph, Bateson points out that this particular image “gave us the first clue for the formulation that the Balinese mother avoids adequate response to the climaxes of her child’s anger and love.” The photograph shows the young girl clinging to her mother’s legs. The mother’s response is “negligent and relaxed . . . her arm scarcely in contact with the girl’s sling cloth.”

Bateson and Mead didn’t look at this photograph and state a theory, citing the photograph as evidence. For them, photographs don’t prove a hypothesis, they provoke further tests of it. The distinction is important. They used the image as data rather than as a self-evident proof. The details of the photographs suggest a general theory or principle. If the principle is in fact general, I will find other versions of it when I return to the field. If I don’t, further details will suggest a reformulation.[4]

This method of using photographs required them to study and compare images in the field. Plate 23, “Hand Postures In Arts And Trance” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p.100-01), for example, contains eight photographs. The photographs show Balinese artists, unlike Occidental artists, accentuating the sensory function in their left hand. Bateson writes that, because this point was not noticed in the field, where they could have checked it further, it “therefore cannot be stated definitely or backed up by native statements.”

To test their hypotheses about temperament and culture, where did they point the camera? Their practice was initially guided by such assumptions as these:

. . . that parent-child relationships and relationships between siblings are likely to be more rewarding than agricultural techniques. We therefore selected especially contexts and sequences of this sort. We recorded as fully as possible what happened while we were in the houseyard, and it is so hard to predict behavior that it was scarcely possible to select particular postures or gestures for photographic recording. In general, we found that any attempt to select for special details was fatal, and that the best results were obtained when the photography was most rapid and almost random. Pls. 71 and 72 illustrate this; the photographer assumed that the context was interesting and photographed as far as possible every move that the subjects made, without wondering which moves might be most significant. (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. 50)[5]

But within these broad outlines, the question remained: where do you point the camera? Though Bateson and Mead continued to have differing opinions about that, in Balinese Character they did it Bateson’s way. He believed in pointing the camera at what he thought was important, and he used the camera to help reformulate what he and Mead thought important or relevant.[6]

Eventually, they pointed the camera at sequences of behavior as a way to closely describe such unfolding interactions as exchanges of glance and gesture. They compared sequences of images from similar events, (e.g., mothers teasing older child with a younger sibling or borrowed baby) with each other, and sequences from one area of social life with sequences from other areas (e.g., mother teasing older child, cremation towers being carried to the cemetery, young girls dancing in trance, and artist’s paintings of their dreams). From these diverse areas of cultural activity and behavior, they arrived at more general relationships (e.g., the Balinese systems of hierarchy and respect).

. . . because of the density of the population and the richness of the ceremonial life, we were able to put together many new kinds of samples. We had not one birth feast but twenty; fifteen occasions, all carefully recorded, when the same little girls went into trance; six hundred small carved kitchen gods from one village to compare with five hundred from another village; and one man’s paintings of forty of his dreams to place in the context of paintings by a hundred other artists. (Mead, 1972, p. 235)

In all, then, they worked at four levels: the individual photograph; the individual interaction described in a sequence of photographs or a segment of motion picture film; the comparison of a collection of sequences, each made of a similar exchange, but at different times and places, involving the same individuals or not; and comparison of collections of sequences, describing different aspects of the culture which might seem superficially separate.

Some Logistical Problems Bateson and Mead Worked With, and How Those Problems Have Been Altered by Technological Developments

Logistical and practical problems arose in connection with three separate activities: making and analyzing the images in the field; moving the materials to New York where they are analyzed again, and shown to other people, though the researchers can no longer return to the original site to “check up a point,” as with Plate 23; finally, editing, summarizing, and combining (recontextualizing) images for a final presentation. Each kind of problem could be solved differently and more efficiently today through the use of digital technology.

Bateson and Mead cut and developed their film in the field, then had their negatives printed and enlargements made and returned to them. Today, skipping the step of printing entirely, one can scan negatives directly into the computer so that they are quickly accessible for study and comparison. Going further, one could use a digital still camera and avoid the use of film altogether. Motion picture film, and video (which was not available to Bateson and Mead), can also be digitized directly into a computer. Digital video cameras, when they are available, will cut out the conversion step.

Bateson complained about the problems of sorting through all the materials when they got back to the United States, and the difficulties of sizing and laying out such a large collection of images for a final printed product.

Selection by size was more distressing. Each plate was to be reproduced as a unit and therefore we had the task of preparing prints which would fit together in laying out the plate. Working with this large collection of negatives, it was not possible to plan the lay-out in advance, and therefore, in the case of the more important photographs, two prints of different sizes were prepared. Even with this precaution, the purely physical problems of space and composition on the plate have eliminated a few photographs which we would have liked to include. (Bateson and Mead, ibid., p.51)

Computers would have solved many of these problems. Providing a flat surface on which the various media Bateson used could be viewed together, stored electronically so that specific pieces can be rapidly located, all this contributing to a more efficient sifting of material, and facilitating the analytical process of comparing and combining images.

A simple example of a computer solution is the size of images. Bateson regretted the small size of the photographic reproductions (the consequences of the economics of book reproduction). But size became a constraint because the readability of an image at a small size became a criterion by which they chose images. So reading in the computer, by allowing viewers to increase the size of a particular image at their discretion, would be an advantage.

Back in the United States, Bateson and Mead asked other researchers from other disciplines to view and comment on the material, after the field work was over but before publication. Mead talks about researchers picking details out of the filmed sequences (”When we showed that Balinese stuff that first summer there were different things that people identified–the limpness that Marian Stranahan identified, the place on the chest and its point in child development that Erik Erikson identified.”) (Bateson and Mead, 1976, p. 40). Today, such collaboration and consultation might well take place (if not now, soon) while they were still in the field by sending visual materials via Internet to New York (or any other part of the world) for other researchers and collaborators to examine.

Bateson and Mead analyzed their field materials, and presented the photographs and text as a rich, layered work. Mead describes the form of the book as an experimental innovation (as it certainly was). Readers then make the connections and relationships the text points out, or follow other paths of association, of potential interest but not pursued by the authors, such as tracing one person through a series of plates (the readers thus making their own paths). Bateson and Mead expected readers to use their formal innovations. They wanted readers to explore the plates for themselves. They cross-referenced images and provided additional information so that readers could create their own combinations of the materials.

Cross references from one photograph to another and from one plate to another have been inserted often, and such insertions often carry implicit generalizations like those implicit in the juxtapositions. To enable the reader to explore the plates for himself, a random supply of cross references is given in the Glossary and Index of Native Words and Persons. As far as possible, native words have been kept within parentheses. They are provided for the use of readers already familiar with Balinese language and custom, and the ordinary reader need pay no attention to them unless he wishes to set side-by-side the various photographs connected with one ceremony or native concept. . . . Similarly, it is possible from the names of identified persons to obtain an over-all view of some of the most photographed individuals, such as I Karba, I Karsa, I Gata, and their respective parents. (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. 53)

What Bateson and Mead wanted to accomplish by combining stills and film can be done today in hypertext. A basic characteristic of hypertext is cross-referencing (as in an encyclopedia, where the end of an entry directs you to “see” related items). Hypertext can be created without a computer, but a computer makes it easier to write and to read. The integration of a variety of media (film, stills, sound) in one document, however, is tied to the computer.

What would a hypertext Balinese Character look like? How would it work? In a straightforward translation you would select a cross-reference Bateson and Mead had designated, not by turning to the indicated page, but by clicking on the reference with your mouse. The designated image(s) would appear for comparison and study. What appeared might be another photograph, a text, motion-picture film, or a recordings of a gamelan orchestra (such as Bateson and Mead used in the film “Trance and Dance in Bali.”)

Bateson and Mead often divided the recording of data, as mentioned above, between film and still photographs. This created problems when they wanted to discuss materials recorded in the two different ways. For example, Plate 42, “A Bird on a String,” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p.138-9) contains twelve photographs of a boy playing with a tiny living bird on a bark string. But the still photographs represent only about half of the entire sequence: “The whole sequence, as recorded in M.M.’s notes, lasted about 15 minutes, but of this period only about 7 minutes was recorded with the camera. At this point the film in the still camera finished, and the remainder of the sequence was recorded with the motion-picture camera.” The second half, on motion-picture film, is thus unavailable in the book, but would be available in a computerized hypertext.

Latour: Immutable, Combinable Mobiles

Two of Bruno Latour’s ideas about knowledge, representations, and power have implications for our understanding of Balinese Character, and for creating and presenting work using electronic imaging technologies, 1) A “shift in thinking” occurs when people put knowledge into the form of “immutable and combinable mobiles”; and 2) “experts [unlike novices] assemble materials in such a way as to make relationships apparent.”[7]

For Latour, representations (”inscriptions”) become sources of greater power when they are mobile (can be moved from place to place), immutable (do not change when they are moved), and combinable with one another (when their size can be “averaged,” their internal relationships remaining consistent) in order to make comparisons.

Such representations become inanimate allies in “agonistic” encounters in which it is not the antagonists’ abilities that matter but the new understanding the juxtaposition of represenations allows: an “average mind . . . will generate totally different output depending on if it is attending to the confusing world or to inscriptions. . . . It is because all these inscriptions can be superimposed, reshuffled, recombined, and summarized, that totally new phenomena emerge, hidden from the other people from whom all these inscriptions have been exacted.” (Latour, 1986 p.11, my emphasis)

To put what we have been discussing in Latour’s terms, the computer screen becomes a “small laboratory” in which previously uncombinable forms or media, such as film and still photographs, may be combined and recombined. This creates the potential for an analytic result which is more than a sum of the parts, identifying relationships (patterns or contrasts) which are visible only because you have combined immutable mobiles. The newly visible relationships drawn from these materials result in a shift in conceptualization, a reformulation of the structure of what you’re looking at. This is the “totally different output” Latour speaks of, which occurs as a result of the manipulation of the laboratory setting.

New knowledge, a new way of seeing the world, results from having an efficient pictorial language and being able to recombine inscriptions gathered from different times and places. Anything that improves this combinability is favored historically because it creates this advantage in power and knowledge. For the same reason, anything that accelerates the mobility of traces without transformation will be favored too.

But inscriptions by themselves are not enough. Latour describes Darwin and other naturalists (using them to exemplify the problems of everyone who gathers data) as being “swamped” in specimens (like Bateson complaining about wading through all the Bali materials once he got back to New York). Having turned things into paper (including photographic images), the analyst now must reduce the amount of paper. A “deflating strategy” is needed. Latour emphasizes what he calls the “construction of cascades,” in which people working with information turn more paper into less paper.

For Latour, good theories, unlike bad ones or “mere collections of empirical facts,” provide “easy access to theory” by assembling materials in one place where “relations between them and hence the answer [the analysis] could essentially be read off from it. Experts [unlike novices] assemble materials to make relationships apparent.” Balinese Character’s presentational strategy makes the relationships between temperament and culture apparent: the photographs, the words, and their arrangement are the analysis, in the sense that their theoretical import can be “read off” the pages. The analysis embodies the theory in just the way that Mead says the Balinese “embody that abstraction which (after we have abstracted it) we technically call culture.” (Bateson and Mead, 1942, p. xii).

Mead and Bateson’s purpose was agonistic in the Latourien sense. They wanted to make an argument about “how character is formed from early childhood to harmonize with values implicit in culture” (Bateson, 1972 p.123) and convince others they were right, thus enrolling them as allies. As Bateson said about the research in Bali, “we assumed that the still photography and the motion-picture film together would constitute our record of behavior.” The combined media would have allowed stronger support (in the form of inanimate allies) for their theories, making a more “expert” arrangement of “allies” possible.

For Latour, the study of signs by themselves obscures the understanding of power. You must study the process that enabled those signs to be where they are, how they are, doing the work they’re doing. “The scale of an actor is not an absolute term but a relative one that varies with the ability to produce, capture, sum up and interpret information about other places and times.” How to dominate on a large scale? “The name of the game is to accumulate enough allies in one place to modify the belief and behavior of all the others.” (Latour, 1986, p. 29 and 31) If visual representations can define a culture (for instance, define what kind of people the Balinese are), then a nationwide magazine such as National Georgraphic is a large-scale actor and an ethnography in hypermedia can become a bigger actor than a book.

Latour points out that, in the case of natural science laboratories, increasing research costs mean that very few scientists can engage in the “proof race.” The social science proof race is quite different. Increasingly, though of course not universally, the new imaging technologies, which make using combined media and hypertext structures less of a tsimmes for anthropologists, are available to “the other people from whom all these inscriptions have been exacted” and from whom they were “hidden.” This makes it possible, at least in principle, for the people social scientists study to construct a counterargument, should at least some of them have access to the appropriate tools and so desire.[8]

Furthermore, the relative inexpensiveness and ubiquity of electronic media and instruments (e.g. the expense of buying a camcorder and making a video compared to the expense of making a motion picture film) takes visual media out of the hands of “professionals” or specialists (and their conventional ways of picturing and deciding what’s worthy of picturing) and increases the number of people who control of them.

Conclusion

Bateson and Mead believed that visual materials were necessary to the full investigation of such subtle relationships as that between temperament and culture. Still photographs and motion-picture film gave them a vocabulary with which to identify and describe those relationships. They intended, though they didn’t have the language Latour later provided, to combine the variety of materials they had gathered (”combinable, immutable mobiles”) in such a way as to provide a compelling demonstration of their analysis, one in which the conclusions could be read off the presentation. They displayed photographs and text together, but could not incorporate the motion picture film, so integral a part of their evidence, with those other materials on one flat surface. In that sense, the construction of what Latour calls the nth+1 cascade, the combination that reduces the bulk of what is to be handled, was impossible for them. Digital imaging and computer based hypertext today make their vision attainable in ways they did not foresee but probably would have appreciated. My guess is that Gregory’s response to these new developments would have been, “Yes, now I can really get busy.” And Margaret’s would have been, “It’s about time, for god’s sake.”